Student Internship position at Refuge Worldwide

Applications are now open for a studio and content based role.

Loading

The Munich-based activist started Statefree to support the millions of people worldwide denied nationality and citizenship rights.

By Chloe Lula

Christiana Bukalo first understood she was stateless at the age of 18.

Born in Munich to parents who immigrated from West Africa without the personal identification they needed to secure German citizenship, she grew up without a national identity and quickly became accustomed to the limitations inherent to her statelessness status.

But it wasn’t until Bukalo attempted to make a solo trip to Marrakech in 2019—her first out of the country—that she grasped the wide-scale ignorance surrounding the concept of statelessness and the degree to which it limited her life. Bukalo was in possession of a travel document that characterized her citizenship status as “XXA.” Hostile border policemen, confused by the classifier, immediately forced her to return on the first flight back to Germany. Devastated by the experience, Bukalo began seeking answers.

The ensuing years have turned her into an advocate for stateless people, of which there are approximately 11 million around the world. Earlier this year, Bukalo received funding for her nascent non-profit Statefree, an NGO dedicated to providing resources for stateless people and a forum through which they can connect with each other and share their stories. We sat down with the activist and entrepreneur to talk about what life has been like as a stateless person, her plans for the platform, and her hopes to change the future of transnational migration and discriminatory border policies.

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself and what led you to open this platform?

I was born in Munich. I’ve always had this sense of uncertainty, but as a child I didn’t think about it too much or too often because our main problem back then was our residence permit, and the fact that we were seeking asylum, which is more important than being German or having any nationality. So the focus was to make sure that we were allowed to stay in Germany. My parents were always in legal consultations and in contact with lawyers who supported us. The most vivid memories I have from that time were staying in an asylum home until I was five, then we moved into a flat. Starting from school, I came into touch with the topic of statelessness more often because we always had issues with my not being able to travel anywhere. There were always these little trips we had to take for school and I couldn’t join. And friends from school started taking vacations and traveling, and at that point I actively started to understand that something was different.

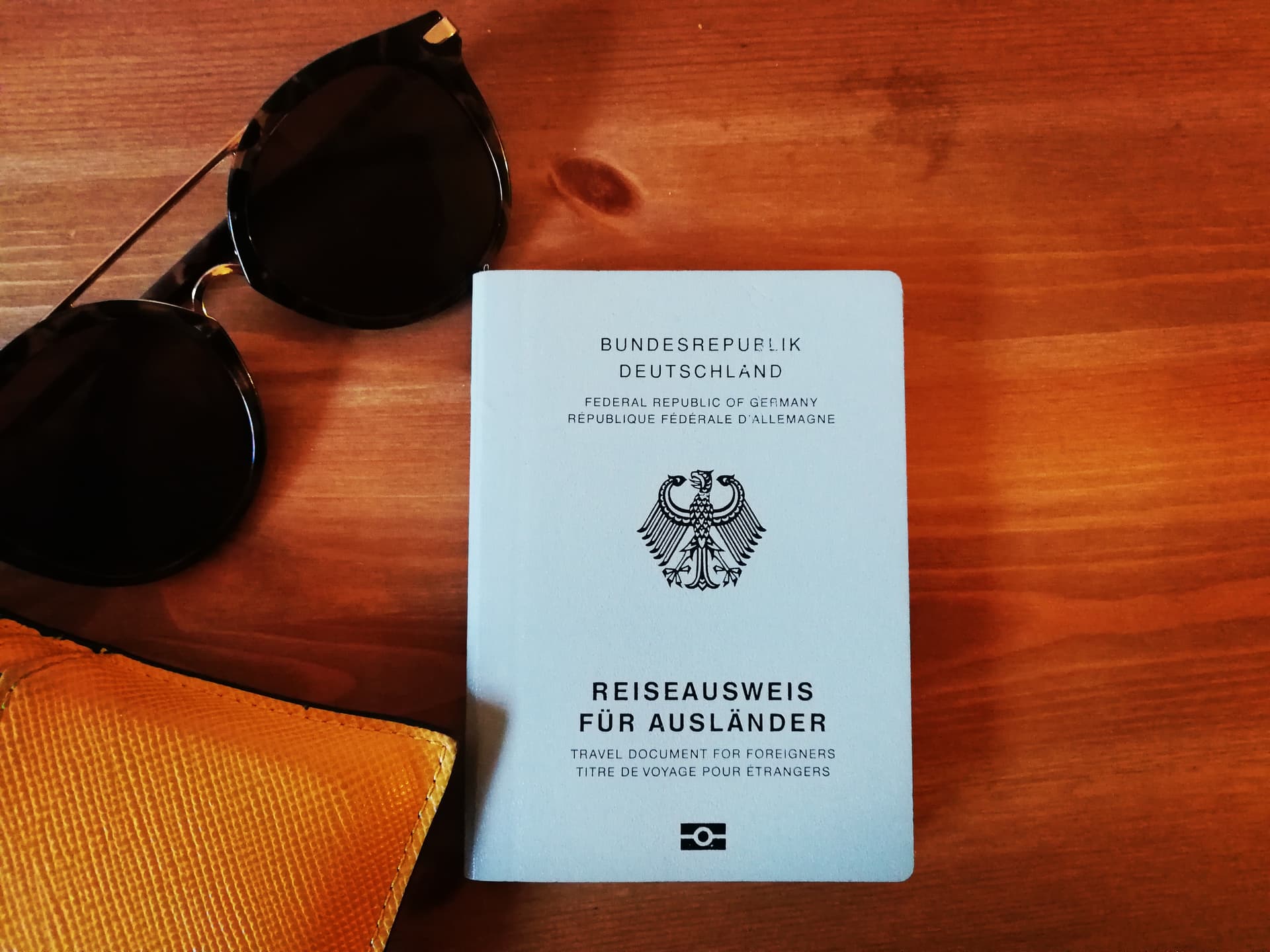

I was 18 the first time I got a travel document. It was called a Travel Document for Stateless People back then. As a stateless person you aren’t allowed to have a passport. In comparison to my friends, I travel once every two years probably. For work I've traveled a few times, but by “travel” I mean that from Munich I traveled to Hamburg. That’s basically it. It’s always uncomfortable for me to travel because it’s always tied to this uncertainty that I don’t know what’s going to happen when security checks my documents. Oftentimes the people checking have no knowledge about it [statelessness]. The document is obviously issued by the state, but authorities working for the government don't get proper education around that, so I oftentimes have to explain this, which is accompanied by a lot of doubts.

I can’t even imagine how stressful that would be.

Yes, borders are very physical to me. Oftentimes people aren’t really sure whether or not to let me in, and honestly I don’t even know! I decided to travel to Marrakech for two weeks. Beforehand, I did a lot of research to see if I was even allowed to travel there. I reached out to the embassy, and they didn’t know what statelessness is. So I flew to Marrakech, and as soon as I arrived, I was confronted with the information that I’m not actually allowed to enter the country without a passport. So that was an extremely traumatic experience. I cried a lot.

A week after I returned, I was extremely upset and ashamed that I didn’t have the necessary information, that maybe I didn’t do my research correctly. I felt like I just needed to make sure that this doesn’t happen to anyone else, and that it doesn’t happen to me again. In my mind, I thought, “Okay. People have created the concept of statelessness, so there must be a global institution that knows everything there is to know about statelessness.” But people really don’t know what it is. On your document, it doesn’t really say “stateless,” it says “XXA.” Try Googling “XXA!” So I didn’t even know the term for it. All I knew was that I was without citizenship.

Before this research, I always thought that me and my sisters were the only ones. If you are affected by something, and you notice that no one else in your environment knows anything about it, then you assume that it’s not really a problem that exists, right? It might be a coincidence, but yours must be a very individual case. I’d never met anyone else who had been affected by this or who even knew about the term. And obviously there were no solutions, so I thought that if there were more people who were affected, then there would be more people taking care of them.

But I found out that there are millions of people who are affected. The estimate I found in 2019 was 10 million, which came from the UN. Then I found an estimate a few months ago that said 12 million. There’s just no sufficient data. It’s extremely non-transparent. It doesn’t make sense.

Is this when you decided to start Statefree?

Kind of. At some point, I realized there is no single source of truth, but there is a lot of fragmented information. So I thought, “Maybe we don’t need another website that just recreates the problem that already exists, but rather points you to the information you need as a stateless person.” When I talked to the different organizations working on this issue, what stood out to me is that there is a lack of communication between these different groups. And that’s how I understood that I needed a platform and a space for people to communicate about the topic, especially for people who are stateless. Because up until now, it hasn’t been something visible. “Loneliness” and “exclusion” are words that definitely come to mind, especially politically. But also in terms of having a community. So maybe there’s no need to feel lonely about this. There are people experiencing the same thing.

I bought the domain Statefree, mostly because I hate that it’s called “stateless.” It already shows that not being a part of the state is something that makes you lose something. Why is it less? Less than what? It’s super wrong, at least in my opinion. At some point somebody sent me a link to Humanity In Action and the Alfred Landecker foundation; it was a fellowship for social change-makers. They were offering a stipend and seed funding. It was great because it would allow me to work with professionals to develop the website. Since then, things have been progressing pretty well. The fellowship started in September. The team grew. Now we’re eight people and we’re working with a web developer. So that’s where we’re at right now.

What are different sets of circumstances that could lead to somebody being stateless?

One of the problems with statelessness is that the ways of determining statelessness often aren’t defined. So it’s oftentimes extremely arbitrary. In my case, for example, when my parents came to Germany, they didn’t have sufficient information to prove their identities. And in order for me to become German, being born in Germany isn’t enough.

Statelessness by birth (or childhood statelessness) is a huge issue. So for me to at some point become German, I’d need to prove my identity. I'm stateless, but before that I just had an undetermined nationality, which is even worse. If you have an undefined or undetermined nationality, you have even less access to rights that other people have, which means it could be even harder to get a travel document, and you can’t apply for citizenship because your nationality is undefined or unclear. The 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons stated that people living in a territory would be protected, and that UNHCR is "tasked to undertake measures to identify, prevent, and reduce statelessness, as well as to promote the protection of stateless persons." So, despite efforts to not reproduce statelessness, states are still reproducing the status of an unclear nationality, which is even worse.

In Germany, you can only apply for citizenship if you’re at least stateless, and you can only get a statelessness status if you can prove that you aren't entitled to another nationality. So you would need to maybe travel to a country you have never been to—and you can’t even travel—to prove that they are not willing to give you citizenship so that the other country can give you a statelessness status. So people spend a lot of money and a lot of time and emotional burden on proving things they can't prove. I’m born here, so there’s no country in the world that has more information about me than Germany.

In other cases, the country you’re born in or are living in isn’t recognized as a state anymore. So that’s the case with Palestine. There are also gender discriminating cases. In some countries, mothers aren’t allowed to pass their citizenship on to their children. A lot of it is that people will resettle to other countries, and those countries don’t want them to have citizenship.

I imagine being stateless precludes you from accessing opportunities and exercising rights and privileges that most people take for granted.

Yes. I'm not sure whether or not I’d be able to marry someone, because oftentimes you need a clarified identity. And I’m also not sure what would happen if I had a child and wasn’t married. I would probably pass my statelessness status on to my child. But other people have worse problems; they’re not allowed to go to school, or they can’t travel at all. They don't have access to public health services. In Germany I do, because I work here, and that’s tied to my working permit and not my nationality.

I’m 27 and I have never lived in another country. I don’t understand what prevents me from voting and participating in society. Stateless people have no power at all. They can’t vote, and then the people who are voting decide who our political parties are, who then determine our access to everything.

In general, things that seem simple to other people are so difficult for us. For example, I really wanted to study communications at a university in Munich, but when I tried to apply for it, they asked for my nationality on the digital form. In the dropdown there was no option for “stateless.” So I just didn’t apply, because I didn’t know how. I knew that asking the people in charge of the program would mean that I’d have to explain what statelessness is, and that even explaining it wouldn’t mean that the problem is solved, because neither I nor them knows whether or not I'm allowed to study at the university.

Other apps require that you prove your identity, and you need to upload your ID to verify your identity. My ID will be rejected 10 times because the system isn’t familiar with it. These are just the small things that are micro-aggressions for stateless people. Nobody understands that we exist.

I know that one goal of Statefree is to find other people to share their stories, and it seems like that would be a very empowering way of taking control of a narrative that’s systematically tried to erase you. Have you had much luck finding people to share their stories? Do you have any plans in place for developing that part of the platform?

Well, right now we only have a landing page! We’re still developing the forum. We’re testing the registration flow and how you post and so forth. We want to have a feed—which is familiar with what we know of social media—and we’ll have another part that’s structured like a forum. Right now our plan is to make the space as comfortable and as welcoming as possible, which isn’t very easy.

Apart from that, I'm getting in contact with other stateless people. I'm getting to know them through online events and webinars. People also reach out to me. ENS—European Network on Statelessness—has also called stateless activists and community leaders to get together once a month to share their stories and updates. And this has been a great process to stay in contact with people who are stateless.

What are some tangible ways that statelessness could be addressed? How do you see the conversation growing and legal rights being expanded to include more stateless people?

That’s a good question. I was avoiding getting into this legal and political space because I'm not an expert—I’m just a stateless person. But right now we are actually starting to think about things we want to advocate for. The terms of becoming stateless are so arbitrary and undefined. In Germany, becoming stateless or getting German citizenship almost depends on the city you live in. This is something that should stop. It should be similar in all cities, and it shouldn’t depend on luck.

Somebody also needs to decide what’s possible as a stateless person. These decisions need to be documented. Why can’t people at the highest levels of decision-making at least try to make the situation as easy as possible for us?

If readers wanted to help or get involved in some way, what would you suggest they do?

I really believe that one of the most important things is spreading the word. I remember that I barely ever told anyone I was stateless. Only my closest friends knew, because it’s not something you just share with anyone. It usually leads to a pretty uncomfortable conversation. There are 126,000 stateless people in Germany. But where are they? Spreading the word can support in raising awareness, increase visibility and potentially even get in contact with other people who are affected by statelessness.

Apart from that, I think that everyone needs to reflect on the topic of national identity as a whole. Is identity really tied to your citizenship? It can be for some, but some people might identify with the country they’re born in, while others identify with the country they now live in.

One thing that’s very important to me is to at least address the fact that my story is one out of many, and that it’s about everyone who is stateless. It’s super hard to understand this topic, and people think this means they don’t know enough about it. But that’s actually not true. It’s hard to understand because it’s hard to understand.

Follow Christiana Bukalo on Instagram. You can visit the Statefree website here.