moe. and Acidfinky to host a fundraiser for Sudan and Palestine

Come down next Wednesday, December 10th.

Loading

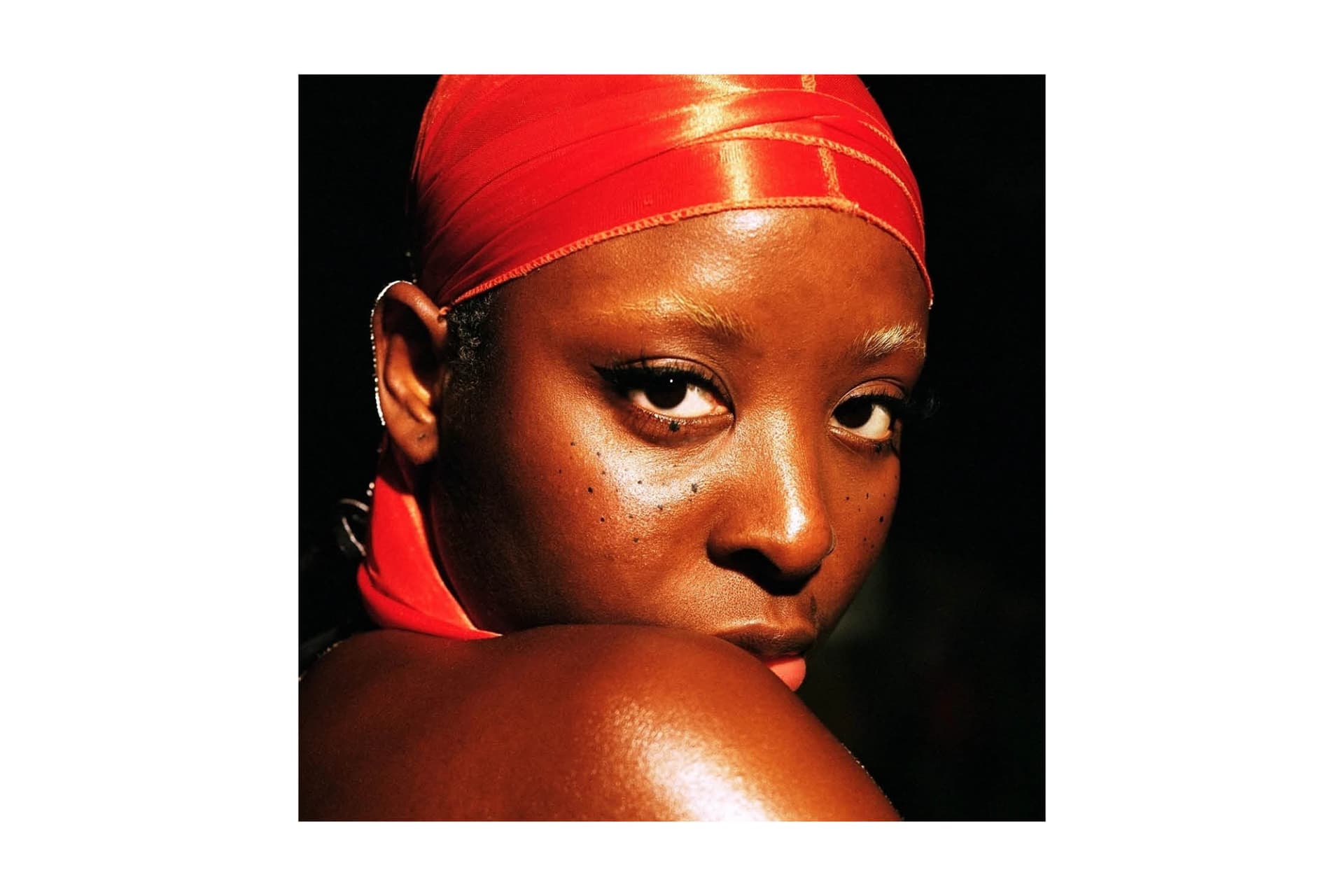

Yewande Adeniran speaks to the founders of Beyond Homophobia ahead of their appearance at Desire Lines.

By Yewande Adeniran

Is Jamaica homophobic or are we viewing the country through a Eurocentric lens?

Perceptions of Jamaica in the West, the importance of self-empowerment for LGBTQ+ individuals in the Caribbean, and the colonial roots of homophobia in Jamaica are the themes that the project Desire Lines seeks to untangle this week at Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

We explored these questions in detail with the co-editors of the multi-award-winning volume Beyond Homophobia, whose joint work builds on years of personal experience and groundbreaking research into LGBTQ+ experiences in the Anglophone Caribbean diaspora: Moji Anderson, who is a senior lecturer at the University of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica, and Canadian writer and lecturer Erin Macleod.

Spanning prose and poetry with contributors from a wide variety of academic disciplines including Ajamu Nangwaya, Rinaldo Walcott, Carla Moore and Anna Kasafi Perkins, Beyond Homophobia aims to disrupt the pre-existing perceptions of the Caribbean as inherently homophobic. This image has been perpetuated by colonial attitudes, homophobia and structural gendered discrimination, as a result of years of Transatlantic slavery and British colonialism. Macleod and Anderson fight depictions of Jamaica and the Caribbean as violent and dangerous for LGBT+ people, which not only erase the voices of people from the large queer community living there but marginalises them further.

Jamaica hums with the sound of bashment, dancehall and reggae, genres that have been hugely influential in the US, UK and throughout the diaspora worldwide. For years however, some LGBTQ+ charities have spearheaded blanket bans of Caribbean music due to fears about homophobic lyrics. This perception of entire genres and movements as monolithic has harmed queer Jamaicans who use music to express their identity.

In the early 2000s, Anderson found herself in the U.K., working with people living with HIV of Caribbean origin, across a wide spectrum of sexualities. It was there that she became interested in their experiences and life stories. After travelling back to Jamaica, where she is now based, Anderson began to write extensively on what she had learned. At UWI (University of the West Indies) she met Erin Macleod – a chance meeting that spawned a fruitful collaboration.

Together, Anderson and Macleod organised the symposium that would eventually lead to the Beyond Homophobia collection in 2020. Anderson recounts the event with great excitement: "It was awesome! It was amazing, there were so many people in the room. The vibe was incredible. People were excited and thought ‘wow, this could genuinely happen?!’"

The absence of space for LGBTQ+ people does not mean that it isn’t wanted or needed – it’s simply a gap to be filled, and their collaborative event proved this. "It was almost like there was a sigh of relief in the room. People felt comfortable. Erin and I were happy with the research that was presented. It was respectful and engaging. That’s when we decided to make it bigger," Anderson explains. “If there are people in society who are stigmatised and marginalised and not allowed to have their own voice or speak their own truth, then certainly as human beings but especially as academics, we want to present an opportunity for those voices to be heard".

Homophobia is an import to Jamaica, forcibly implemented during slavery and British colonialism. There is nothing about Jamaica that is inherently homophobic. Speaking of her research once more, Anderson invokes the term homocolonialism. This is the imperial need and drive to define those who are considered colonial subjects. The need for Jamaicans, and formerly colonised people across the world, to tell their stories is now more pressing than ever.

Those who are not familiar with the day-to-day experiences of queer Jamaicans are often the most vocal, due to their privilege of residing in Western countries. Those among us who are active on parts of the Internet where LBGTQ+ African and Caribbean people are building online spaces, and in turn offline communities, know that marginalised groups have always found ways to exist together and create moments of joy and happiness. As Anderson points out, "through our separate experiences, we’ve had a lot of insight into the fact that people who are not heterosexual in Jamaica are living their best lives. That doesn’t mean there’s no homophobia or transphobia, that would be impossible to say."

Throughout her work in London with Caribbean people and in Jamaica, Anderson found that even in the context of official and performative homophobia, people still find ways to navigate and have fulfilling lives. Pushing back against the external narrative that’s been imposed is a key way of challenging people’s perceptions. "You can’t tell us who we are or what Jamaica is like for those who aren’t heterosexual," Anderson says.

"Who are they to tell us Buju Banton can’t travel and perform?" asks Anderson. Since the start of the millennium, the U.K. has banned artists including Banton and Beanie Man from performing anywhere. With a report into LGBT+ hate crime in the U.K. by the charity Galop stating that 3 out of 5 LBGT+ people have experienced violence relating to their sexuality or non-conforming genders, the hypocrisy of the U.K., which presents itself as a safe place for queer people, is clear. These bans serve to reproduce the same dynamics that were created centuries ago. Anderson declares: "It is unfair and racist. There is a very important political point to what we’re doing that is anti-imperialist and decolonial."

Macleod points towards examples of the monolithic attitude of superiority in white activist society: "white LGBTQ+ organisations who are ‘supposedly’ attempting to speak out against homophobia, end up missing who they should actually be listening to because white people are just listening to ourselves."

Macleod continues: "I remember back in 2004 when there was initially the 'Stop Murder Music' campaign zine with Peter Tatchell. In that there was a commentator named Richard Burnett, who wrote this cover story called 'what happened to one love?' and identified all these dancehall artists that he deemed to be profoundly homophobic." This triggered years of campaigning and articles in the British and Canadian press, supported by the Green Party of England and Wales. Paraphrasing a quote from the zine, Macleod retells of the blatant and prevalent anti-Blackness: "You keep that back on your island."

It is this cognitive and historical discrepancy that gave birth to the name Beyond Homophobia. "When you focus on homophobia, what you’re doing is centering attitudes that stem from the colonial system. Even if you try to fight that as a member of an activist organisation in the so-called West, you end up centering the same colonial position that has caused this in the first place, rather than listening to people within Jamaica," Macleod explains. Although around twenty years have passed since Tatchell’s zine, media platforms are still showcasing the same rhetoric, which has the potential to influence current and future generations.

Documentaries concerning the lives of LBGTQ+ individuals across the globe are a rare occurrence, but when Great British Olympic diver Tom Daley’s one-hour-long feature, 'It’s Illegal To Be Me' was broadcast on BBC One in conjunction with the Commonwealth Games, there was scope to accurately represent those living in Commonwealth countries where being gay is punishable by law.

But this opportunity was missed. Referring to the broadcast, Macleod speaks of Daley’s simultaneous confrontation of his own biases and gaps in his own knowledge of other LGBTQ+ people around the world: "He is forced to come to terms with his utter disrespect of queer communities in other commonwealth nations around the world and his own thinking that him being the person who is being focused on gives him assumed knowledge on the topic. He is occupying the same position as Peter Tatchell by focusing on the homophobia and not the people there," she says, adding that "the idea of going 'beyond' homophobia, beyond monolithic views of places outside of white western understanding, to me is extraordinarily important."

Beyond Homophobia and avenues like it provide a platform to connect, build and learn from one another, but without the support and adequate infrastructure, their existence is at risk.

Anderson points out that getting started wasn’t too difficult, because the need for a project like Beyond Homophobia to provide physical space for Caribbean and other non-white people to tell their stories was pressing: "There’s nothing like it. There is something really powerful about this collection and by extension the conferences. The reason we were able to do it was because there were people before doing the work. This is what we’re building on. What we did was provide a big space and a couple of days for those people to come together."

Macleod adds: "People have always wanted to connect and there have been previous opportunities, but the question is infrastructure and capital and if they are able to support this. Having the University of the West Indies, which isn’t the most wealthy institution, channelling money into getting a scholar like Rinaldo Walcott to speak is important. This is what activists in the U.K., Canada and the U.S. need to know."

To create change, we need to focus on the positive experiences of being queer in the Caribbean. "That’s what you should focus on." Macleod explains. "You don’t punish and boycott and ban. You support, nurture and address the positive. Demonisation and the existing ‘keep that shit on your island’ attitude is just going to maintain the same cycle."

Images:

Desire Lines, Stills from research, Kingston, 2022, Courtesy Shade Lane Productions, Design: NODE Berlin Oslo.

Simone Harris as medium for Lady Blake Ophelia Stratum, 2020, Photo: Lisa Chang, Jamaica. Courtesy of Simone Harris.

'Troubling Identities' (Multimedia – Digital Collage Art & Poetry) by Angelique V. Nixon

Sippin’ T

LaLoVe´s Kitchen: La Gran Drama-Tisch photos by Dico Baskoro & Agostina Cerdán (2021)

Come down next Wednesday, December 10th.

This week: Gaza Biennale, embodiment workshops, listening sessions

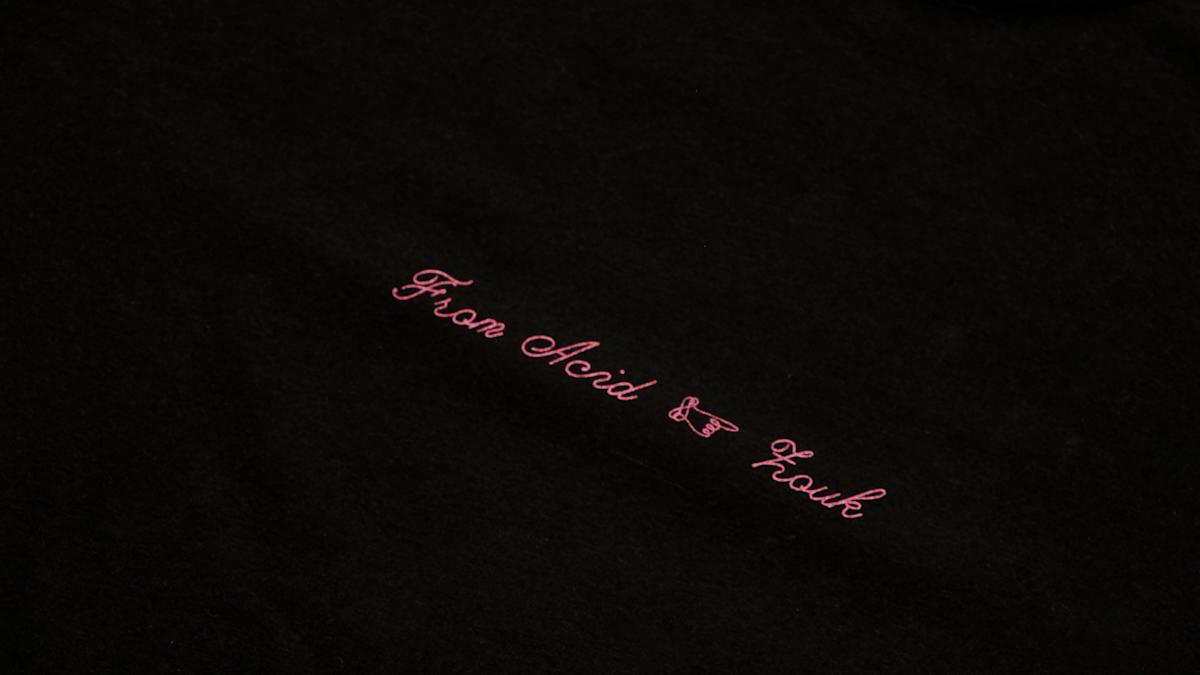

Out now, featuring every genre we've ever had on the radio.