Berlin Stories

This Week: Fête de la Musique, United for Gaza, Afrolution Festival

Loading

An interview with Majazz Project, Shasha Movies and Hopscotch Reading Room.

By Tiffany Lai

Over time, memory fades and we reach for materials to help narrate the past. Archives can hold the key to what communities deem worthy of preservation, what they see as history.

Mainstream archives re-produce mainstream narratives and the influence of some stories over others can result in erasure or cultural forgetting. Alternative archives, therefore, expand our view of what could be, by changing our conception of what has been. Re-envisioning histories through archives can produce new imaginaries of the future.

Tiffany Lai spoke to three individuals who use archives in their professional and creative practice, asking them the same four questions:

What is an archive to you?

How can the act of archiving challenge mainstream narratives?

How are archives changing in the face of technological advances?

How can people bring archives/archiving into their daily lives?

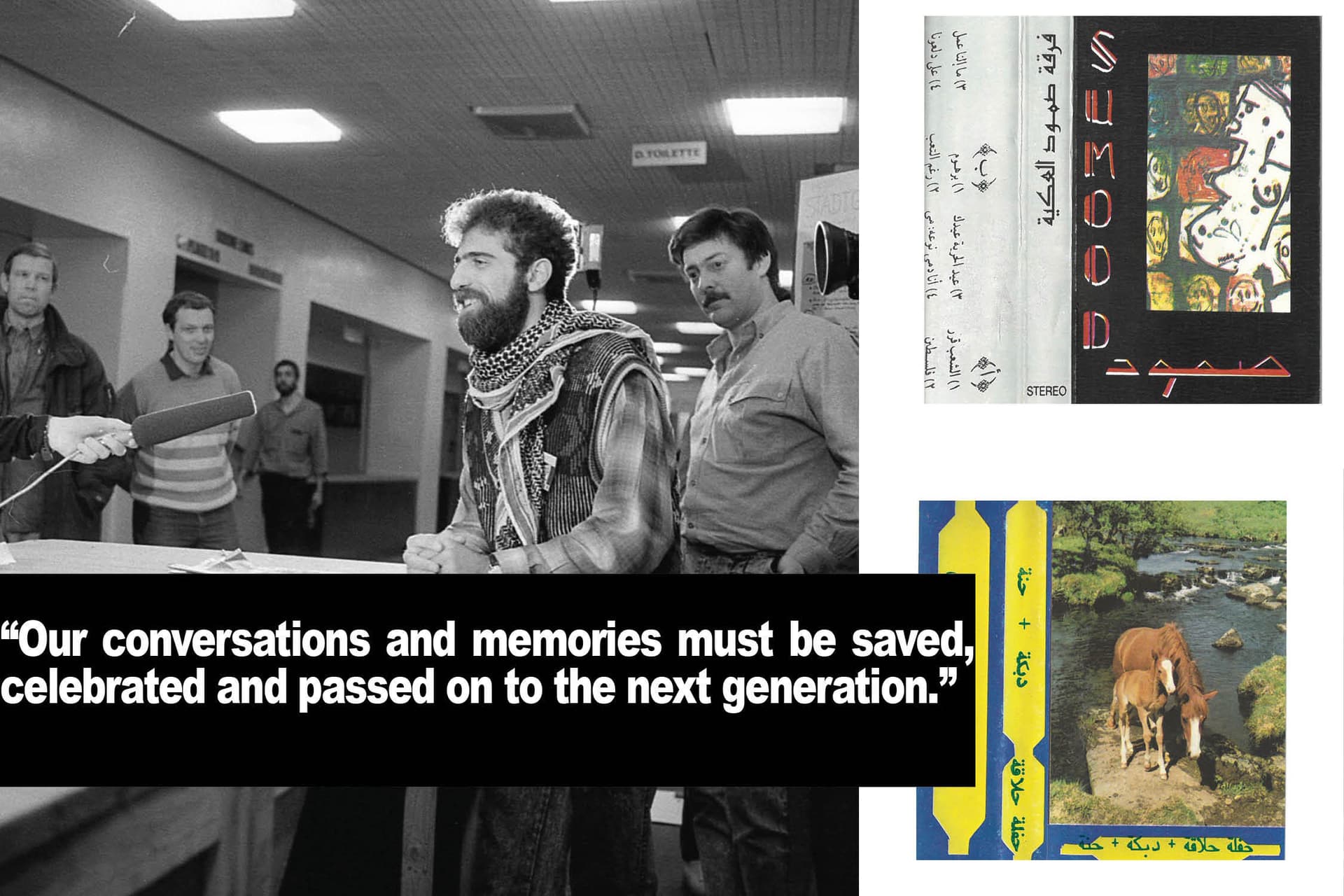

Mo’min Swaitat, founder of the Majazz Project, a record label and research platform dedicated to vintage Arab and Palestinian sounds.

As the owner of the first Palestinian reissue music label, the archive for me is a non-stop research project. We are dedicated to telling the story of the Palestinian lost archive - we’re interested in the music and the artists behind the work to give the music a new life.

I also strongly believe that these kinds of stories must be told by people who have a personal connection to the material, so as to avoid misinterpretation and orientalism in exchanges between the West and the East.

The art of archiving has come back at just the right moment, it marks a return of emotional, warm spaces and stories. Our conversations and memories must be saved, celebrated and passed on to the next generation.

Bella Barkett, film programmer at Shasha Movies, an independent streaming service dedicated to new and archival films from South-West Asian and North African cinema.

Archives to me are a way to connect, to learn and to challenge. Whether it’s a shoe box, a diary or a film roll, the archive stored in one object has the power to move the individual consciousness to realms of generational suffering, injustice, strength and courage.

One of the core memories from my youth is of my dad telling us about the various films that he would see with his friends at a cinema on Hamra Street, a trendy stop in downtown 70s Beirut. Many of these films were made in Lebanon prior to 1975 and their histories have since been lost due to structural and environmental issues. For example, the lack of investment in proper storage facilities, films lost to censorship and the ravages of conflicts are all partly to blame. These collections, which are hardly known, are at risk of disappearing altogether, so archives are crucial to our ability to research and develop understandings of a communal identity.

The world of archives no longer just consists of scholars but rather has an audience whose members have varying levels of expertise, expectations and cultural backgrounds. This new audience is more focused remote access. As a result, a beautiful thing has occurred in the last few years - new ways of interacting with digital archives have developed, whether for personal projects or reconnecting with families.

Archives have been forced to face new interactions and challenges. The scope for which we can interact with archives is ever-increasing, which further unlocks the potential of what an archive can, and will do.

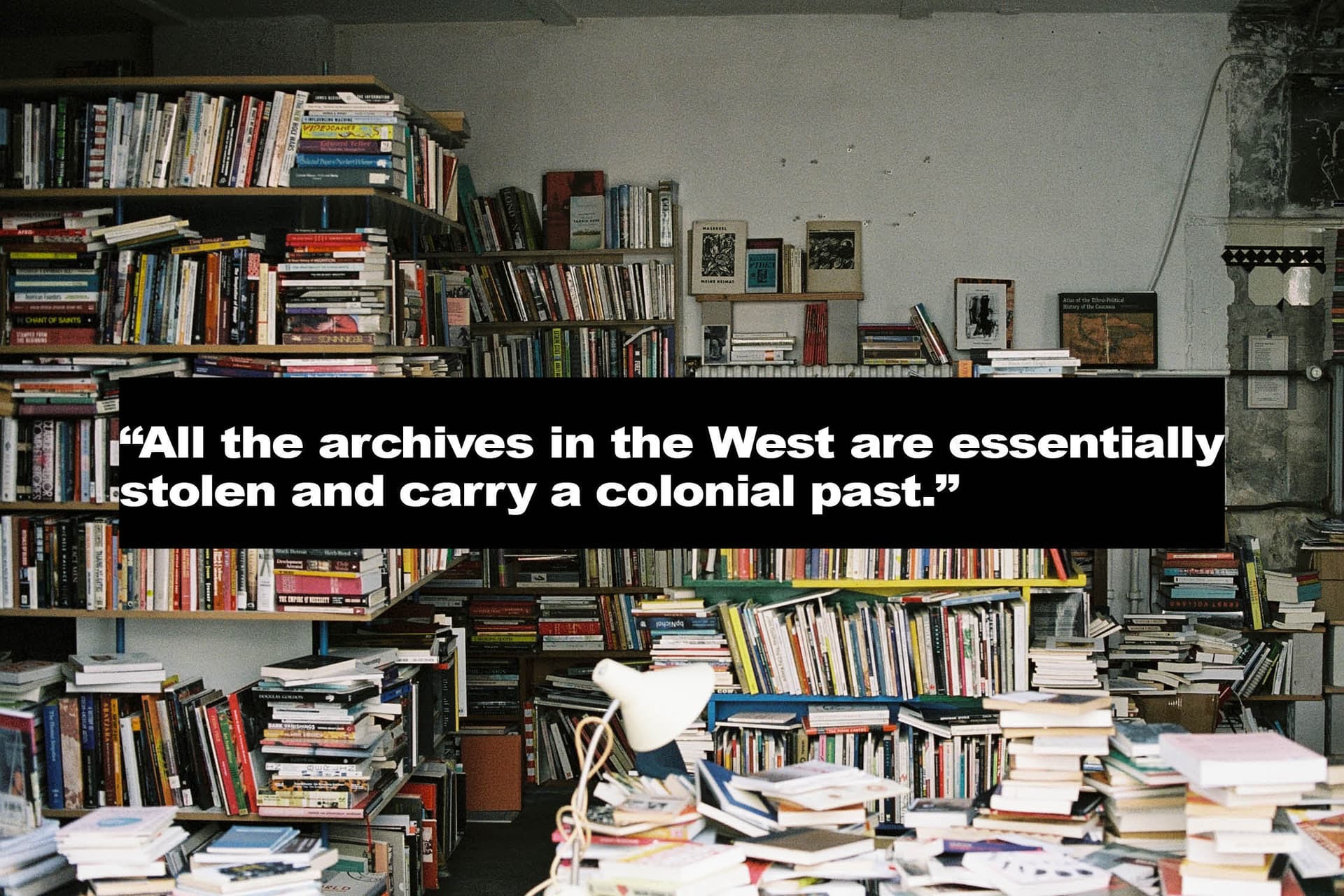

Siddhartha Lokanandi, owner of Hopscotch Reading Room, a non-Western and diasporic bookshop based on Kurfürstenstraße, Berlin.

I think it’s interesting you use the word archive. Archives like mine or Shasha’s are more akin to repositories of interest and passion. Historically, archives are more systematic than that. Because of that history, I’m careful not to valorise archives.

All the archives in the West are essentially stolen and carry a colonial past. If we think of the Phonogram Archive in Berlin, (a collection of ethnomusicological recordings), it’s an archive of sounds deposed from their source. It’s full of sounds recorded in India or Africa because cinema and sound recording came on the coattails of colonialism. As soon as the technologies were developed in England, they spread to the colonies. That's why India has as much of an active cinema tradition as England.

I think it’s important to problematise and probe archives. Admittedly, you could say I have an archive here at Hopscotch. I trawl blogs and social media for texts, I chase them down online and bring them here to Berlin and that is the archive in one sense. But through that archive, I’m looking to elevate the idea of the diaspora, especially one that is at odds with the German idea of the diaspora. So a lot of what I do is at a 90-degree angle to official discourse.

For me, each person comes with their own cultural baggage and since we can’t step fully into each other’s shoes we need to interact more with each other’s worlds—we can do that through books. When some people come into this bookstore there is an intense and visceral sense of recognition when they see certain books, sometimes verging on sadness. People have broken into tears before. I’m committed to trading in those moments of recognition and then hoping to regenerate or change something.

Globalism is an archive of loss, diaspora is its record. Some of it is self-validating and championing and some of it just weighs you down. So the game is to figure out the axes of that scale and then celebrate it. In the past, a lot of texts have been focussed on the awareness of loss but now we're in an age of making something of that loss and regenerating ourselves.

Design by Kolja Tinkova.