Feministischer Kampftag 2026

Various crews and activities are representing at Niemetzstraße this March.

Loading

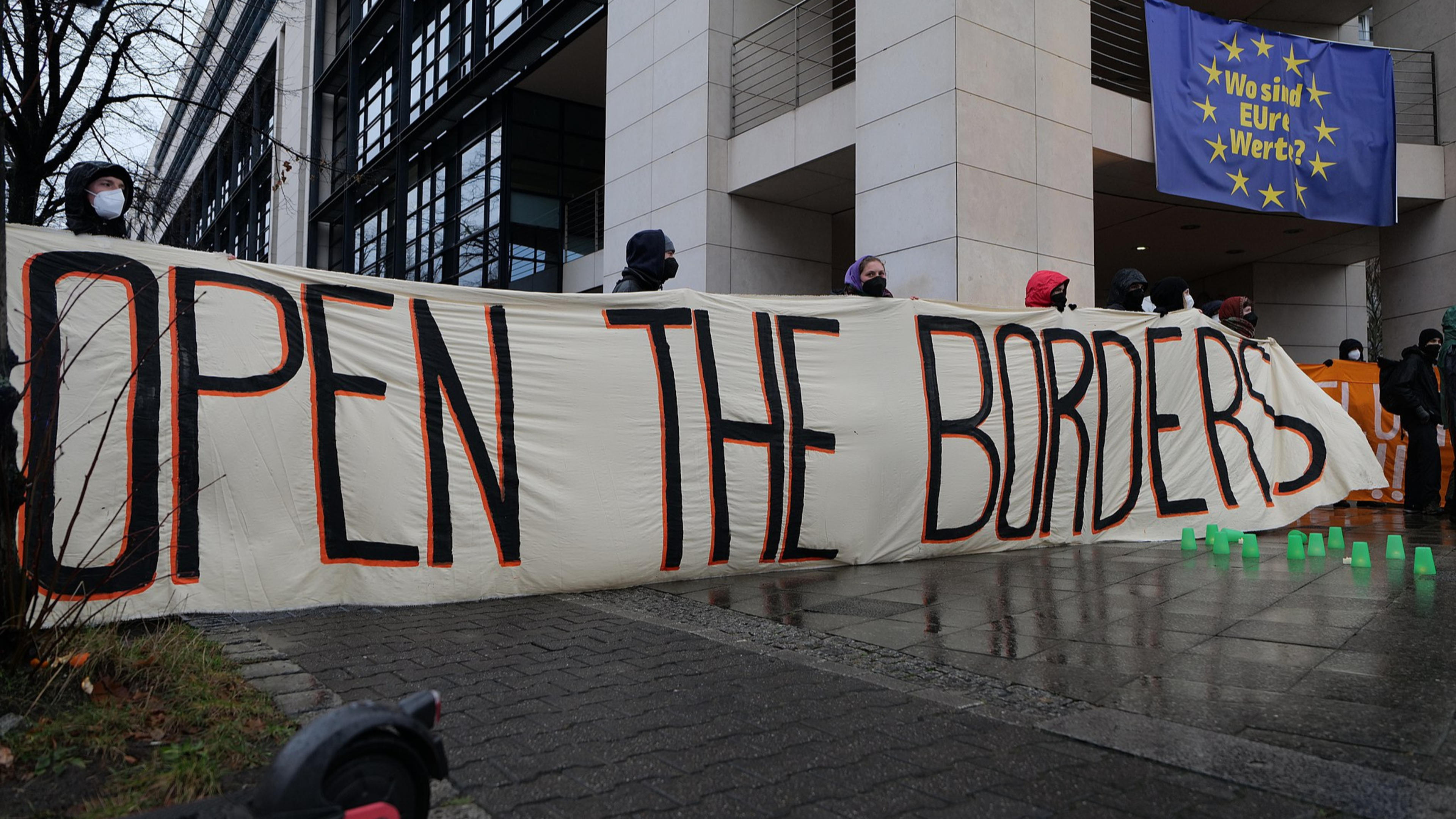

There are a handful of people risking arrest to help migrants stranded in the Bialowieza Forest National Park. One organizer tells us what it’s like.

By Joshua De Souza Crook

Locals are stepping up to help refugees trapped in the Bialowieza Forest National Park.

Heavily-armed army vehicles now patrol what has become the emergency military zone since September. There is a strict no-entry ban for media and NGOs, with only local homeowners and special personnel permitted access. This has resulted in residents turning into overnight activists as the only source of help for thousands of fleeing refugees.

Bialowieza Forest National Park is the largest and oldest forest in Europe. It is the last primeval forest on the continent—an open mass defined by swamps and fallen trees. Even for experienced hikers, the forest presents challenges. For refugees seeking passage, the forest can present potentially fatal encounters. Ola, who has requested to omit her last name, lives 300 meters away from the Belarus border. She has been a focal figure in providing support to the thousands of passing refugees since the crisis developed over the summer. The border crossing recently became the preferred route for an influx of Iraqi Kurds and Syrians hoping to enter the EU Bloc, but Ola has also helped travelers from Yemen, Congo, and Nigeria. Poland is reluctant to grant these people legal refugee status, so they have become political pawns that are continuously pushed back into the Belarusian side of the forest—a no-man’s-land. The crisis has been simmering for months, but now it’s on the verge of becoming a humanitarian disaster.

The crisis has divided Ola’s small village into three groups. There is one group trying to help the refugees. Then there is an elderly group who are either scared or concerned about the developing situation. The final (and most visible) group is actively looking for refugees to report to the border guards. “The forest is a blessing and at the same time very dangerous just to be there for a couple of days,” Ola explains. She once helped a group stuck in the forest for over three weeks seeking safe passage out of the military zone. Most groups pass through the forest within a couple of days to their connecting transport on the other side, but countless others are caught and detained by border guards.

Spending her time between Warsaw and the forest, Ola built a countryside getaway a few years ago with some friends to escape from the city. Today her home is the headquarters of their initiative and a warehouse that supplies refugees. No NGOs or charities are allowed to enter the zone, but Ola and ten others supply essentials such as food, clothing and aid to the refugees. They also provide guidance for safe passage through the forest. Occasionally they act as the legal representatives of the captured refugees. They have partnered with Grupa Granica, a group of 14 different NGOs that teamed to support those at the forefront of the crisis.

“There are police checkpoints everywhere. It is essentially impossible to pass unless you show the right papers,” Ola explains. “Not even our distant family can visit. I see over 25 large military trucks driving through my village every day. There are helicopters, drones, military men with big guns, and there is a lot of border guard presence everywhere. The atmosphere has changed in the village, it feels like you live in a warzone.” This has split locals, pushing many into anti-immigration and anti-refugee groups. “Unfortunately, this group will actively go into the forest to search for refugees and call the border guards,” Ola says. “They also keep an eye out on their neighbors, and if they see anything suspicious, then they will also call the border guards.”

“I have a neighbor who will drive around my house three times a day, he’ll be looking very suspiciously inside to see what is happening in my backyard,” she adds. “He’ll look into my house to see if we are looking after people. I feel like they are watching me constantly.” Helping refugees comes with consequences, often involving an invasion of privacy by others in the village. “In one situation, we were trying to help a family of seven people who had two little girls with them. They must have been 2 and 5 years old,” she says. “We gave them food and clothing, then showed them the way out of the emergency zone, and when they left and went to the forest, our neighbors ran out of their homes and after the refugees to see where they were going and then called the border guards. They came and picked them up and then drove the group deeper into the forest.”

The forest can be a lawless environment where border guards and the military bypass international law. On top of forcefully pushing refugees back into Belarus, military also transport them even further into the forest to disorient them. Ola has witnessed many confrontations between refugees and Polish forces. She says these encounters are “very unpleasant.” She recalls seeing a family of nine people from Iraq, including a pregnant woman, an elderly person and two teenagers with border guards. “We saw them when the border guards were already with them. At first, the guards were fine with us providing some food and talking to them a little bit,” she explains. “But when we asked if they wanted to sign papers for international protection, and if they wanted us to be their legal representatives so that later on we could enquire about them legally or go to court on their behalf, then the border guards switched. They wouldn't let them sign the papers or even let us pass the papers to them so they could apply for legal rights.”

Ola wanted to record the refugees saying that they were in Poland and that they wanted to apply for national protection, but the border guards didn’t allow her to. Instead, they packed the migrants into a van and drove them away. “We didn’t know exactly where they were taken. One of us tried to follow in another car but that person was stopped by the police on the border between the emergency state zone and the regular area,” she explains. At that point, they lost sight of the border guards.

Ola says this is one of the border police’s regular tactics. She adds that ambulances can’t legally enter the forest. In emergencies, refugees will leave the forest’s relative safety to seek medical attention. “But we would then need to monitor the situation as the border guards would often come to the hospital to collect the people who just got to the emergency room three or four hours earlier,” she explains. The guards would hastily take them in their vehicles and drop them off even deeper into the forest. This breaks almost every human rights law that exists, she says. Dozens of bodies have been found in the forest since the crisis began.

In recent weeks, the border guards and paramilitary have become increasingly heavy-handed with people helping refugees. Ola recalls an incident where one of the volunteers, who is also a translator, was forced out of his car by a paramilitary organization called the Territorial Army. “These people are not professional soldiers, but they are in the area to help the soldiers. They are usually young and inexperienced people who like the idea of holding a gun but have no idea how to handle these situations,” she says. They stopped his car on the road and were very violent, accusing him of people smuggling. There is little to no accountability when these governmental forces overstep their legal rights, she says.

Poland’s police-military actions are not damaging Belarus or President Alexander Lukashenko as intended. “They are targeting these poor people and treating them like ping pong balls back and forth. What they are doing doesn’t make any sense at all,” she explains. “It is counterproductive.” She says the area now feels like “being part of a forgotten part of the country left to its own devices,” a lawless reign where the end seems nowhere in sight. This disconnection has encouraged the military and government forces to ignore EU regulations and treat these refugees however they see fit as the world is not watching.

“No psychologists or doctors are helping in the area. Instead, all of this has fallen on us, a very small group of people,” she says. “Any normal or responsible country would allow experts and professionals into the area to help,” she explains. Instead, she has witnessed the crumbling of international law and the rise of the military state. The architects of the crisis have created a situation destined for failure. If governing bodies fail to acknowledge this ongoing crisis, it will result in helpless refugees being forgotten and seeing their rights stripped away from them by brutal authoritarian forces.

Various crews and activities are representing at Niemetzstraße this March.

This week: listening sessions, Palinale, lunar new year

Catching up before Heavy Feelings & Refuge Worldwide takeover at Open Ground