Student Internship position at Refuge Worldwide

Applications are now open for a studio and content based role.

Loading

Ciocia Basia face the challenges of war in Ukraine and restrictive German abortion laws.

By Madeleine Pollard

Berlin-based abortion activist group Ciocia Basia has had to adapt to a lot of “new normals” in recent years.

First came the pandemic, which made it harder for Polish people with unwanted pregnancies to travel to neighbouring Germany to access surgical abortions. Then came the October 2020 ruling of the Constitutional Tribunal that made abortion due to severe foetal defects unconstitutional, tightening Poland's already draconian abortion laws.

When Russia invaded Ukraine at the start of 2022, refugees who fled to Poland found themselves deprived of reproductive rights the moment they crossed the border. And 2022 also saw Justyna Wydrzynska become the first pro-choice activist to face criminal charges for facilitating abortion in Poland, increasing the risks for activists like her.

“At every stage I have to tell myself – ok, this is the new normal, get used to it. Looking back at all these crisis situations, we’ve somehow managed to work through each one,” says Zuzanna Dziuban, a cultural scholar from northern Poland, who’s been volunteering for Ciocia Basia since 2018. She is one of 19 members of the Berlin-based group, established in 2014 to help people in Poland with unwanted pregnancies access safe abortions. Its name is a diminutive drawing from a traditional Polish name – “the idea is that you can put it in your phone and it doesn’t look suspicious because everyone in Poland has some Auntie Basia."

Many of the calls Ciocia Basia receives are from people in the early stages of pregnancy who need help obtaining pills for medical abortion at home. Part of the Europe-wide abortion rights network Abortion Without Borders, Ciocia Basia directs many callers to its sister organisation, Women Help Women. But if the pregnancy is over 10 or 11 weeks but under Germany’s 14-week limit, Ciocia Basia arranges for clients to travel to Berlin to have a surgical abortion there, covering the cost of the procedure and other expenses. Its volunteers offer everything from funding and translation to appointment bookings, overnight accommodation, and emotional support. Between October 2021 and October 2022, they helped 128 people from Poland access safe surgical abortions.

Poland's reproductive rights crackdown

The demand for Ciocia Basia’s work intensified in October 2020 when Poland’s right-wing Law and Justice party (PiS) voted to remove the foetal defect clause, imposing a near-total ban on abortion by making it legal only in cases of rape, incest, or when the person’s life is at risk. The law, which came into effect in January 2021, prompted widespread outrage and protest across Europe.

“The ruling of the Constitutional Tribunal totally changed the landscape of access to abortion in Poland,” says Dziuban. “It’s not just about abortions on demand now. More and more people travelling abroad have wanted pregnancies, but are seeking abortions due to foetal abnormalities.” The team had workshops with counsellors to help them prepare for this new wave of clients. “It’s a totally different conversation when it’s a wanted pregnancy. It’s a totally different language you have to use, totally different emotional labour that you have to perform.”

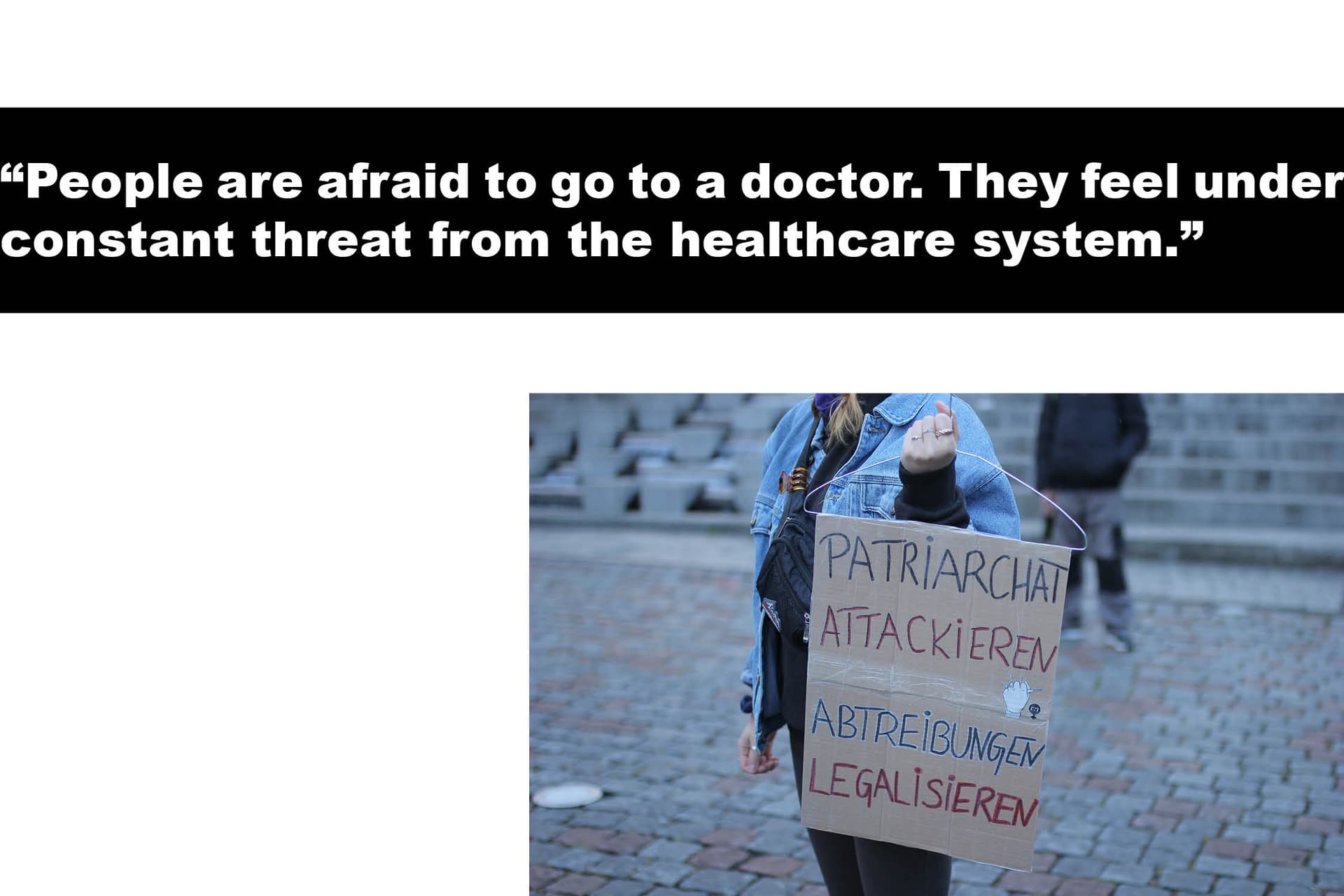

In 2022, the Polish government went further by introducing new measures obliging healthcare professionals – from gynaecologists to dentists – to register all pregnancies and miscarriages. Ostensibly intended to update national health records, this centralised register allows the government to monitor the outcome of pregnancies and identify illegal abortions conducted both in Poland and abroad. “People are afraid to go to a doctor. They feel under constant threat from the medical healthcare system,” says Dziuban. “The government has created an organised system that forces people to lie. It’s unbelievable where all of this has ended up.”

Ciocia Basia’s volunteers are used to navigating the emotional hardship that comes with these measures. While guiding people in Poland through at-home medical abortions, they are available by phone or email at every step of the process, sometimes exchanging 100 messages with one person in a single evening. “There are those who write to you every five minutes and send you pictures of everything,” she says. “We see a lot of embryos and sanitary pads in our activism, and a lot of toilets as well.” Dziuban looks to other members of Ciocia Basia for her own emotional support. “If it gets too much, we go to each other. We vent, we cry, sometimes we laugh because it helps to discharge the tension.”

Arrivals from Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has impacted Ciocia Basia dramatically. Ukraine was known for its comparatively liberal abortion laws, with abortions legally provided upon request for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. While neighbouring Poland provides a place of relative safety for refugees from Ukraine, they are now subject to PiS’s repressive reproductive laws, increasing demand for Ciocia Basia and its sister groups. From March 2022 to October 2022, Abortion Without Borders helped 1,515 people from Ukraine access abortions.

For Dziuban, the new reality set in during a conversation with a Ukrainian woman in March. “She wrote that she'd been in Poland for a few weeks, and had just learnt her husband was killed, and couldn't carry the pregnancy to term. I shed some tears, informed her where to order pills, and realised that conversations like this would happen from now on.”

Among the refugees that Ciocia Basia tries to help, many of their unwanted pregnancies are the result of rape. Although abortion in these circumstances is technically legal, the requirement for rape survivors to show proof of rape and a certified letter from a public prosecutor makes it nearly impossible. “In Poland, you theoretically have access to abortion in this case, but very theoretically,” says Dziuban. “According to government numbers, an average of just two people per year are allowed access to abortion because of rape – this number is a total fiction.” There are even cases of refugees returning to Ukraine to carry out their abortions there.

But Dziuban and her fellow activists are cautious of excessive media attention on this topic. “We get asked about Ukrainian victims of sexual violence as though they are more deserving of abortions than other people,” says Mara Clarke, founder of the UK’s Abortion Support Network. “These aren’t the only refugees we’re helping, these aren’t the only traumatised people we’re helping. Any situation that prioritises one group of people over another lead to bad legislation; this idea that you can have an abortion if. No – you’re either pro-choice or you’re not, and it’s the choice of the person who’s pregnant.”

Legal repercussions for Polish activists

In cases of illegal termination in Poland, the patient is not subject to a criminal penalty but any medical personnel carrying out the procedure are. Justyna Wydrzynska, a member of Ciocia Basia’s sister organisations in Poland, Abortion Dream Team and Kobiety w Sieci, is on trial in Warsaw after being accused of helping a woman in an abusive relationship end a pregnancy with pills. The first activist to be charged in Poland for facilitating an abortion, Wydrzynska faces up to three years in prison.

Even activists working outside Poland becoming worried about being caught up in the country’s legal system. “It’s a shocking development for us,” says Dziuban. “It’s a means to intimidate and discourage people from supporting others in accessing abortion. They will never succeed, but a lot of our energy is associated with this case.” She sees this as further evidence of how the Polish state “criminalises empathy and solidarity”, pointing to the criminal charges being brought against activists for helping migrants cross the Belarusian-Polish border.

There is further worry among activists about the presence of Ordo Iuris in the courtroom, the ultra-conservative Polish Catholic think tank that has been spearheading efforts to roll back women’s and LGBTQ+ rights for years. “The judges are not objective at all,” Dziuban adds.

As the case continues this year, with more hearings added due to witness absences, anticipation is growing. But Clarke articulates a glimmer of hope: “This trial has meant that the pathways to safe abortion are getting promoted more and more across Poland. There are now international eyes on the Polish government's failure to care for pregnant people, as well as more knowledge of where people in Poland can go to get abortions.”

Germany’s flawed system

For Dziuban, a certain “paradox” hangs over the work of Ciocia Basia, which is rooted in the barriers to abortion at home in Germany. Abortion is technically illegal in Germany, criminalised under Paragraph 218 of the German Criminal Code, which dates back to Nazi-era social policy. It can be carried out without punishment during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy (14 weeks since the last period), provided a mandatory counselling session takes place and is permitted at a later term if the pregnancy poses a health risk. “Help is criminalised in Poland, but you can still have your abortion without legal consequences. In German law, having an abortion outside of the medical system is criminalised full stop,” Dziuban explains.

One of the many hurdles to obtaining an abortion in Germany was paragraph 219a of the criminal code, which stated that anyone who publicly "offers, announces [or] advertises" abortion services can face penalties of up to two years imprisonment or a fine. This clause was scrapped in June 2022, but activists won’t celebrate without a total transformation of the law.

“Scrapping 219a has been more symbolic than tangible,” says Lana Saksone, a doctor and representative of Doctors for Choice Germany (DfC). “They’ve left 218 in the criminal code, there are still no protection zones for practices providing abortion care, and the anti-choicers are getting bolder.” She points to an abortion clinic that opened in Dortmund last December, where death threats were sent to doctors, nurses and technical staff. “Abortion is still illegal and stigmatised in Germany.”

Established in 2019, DfC is a network of physicians, medical students and other health professionals who campaign for autonomous choice in all areas of sexuality, reproduction and family planning. “There was this feeling that reproductive health is not important at all in Germany,” says Saksone. “Contraception is not paid for by health insurance, and abortion is criminalised; no one is obliged to teach it, no one is obliged to learn it, and no one is obliged to provide it. We thought that was an unacceptable situation.”

As the majority of medical institutions and universities don't teach abortion – not even to gynaecologists – DfC participates in scientifically recognised “Papaya Workshops” to provide medical students with basic abortion training. Due to its shape, size and texture, a papaya is used as a model of the uterus, enabling students to practice vacuum aspiration, the procedure that uses a vacuum source to remove an embryo or foetus through the cervix.

DfC is also opposed to mandatory counselling sessions that take place three days before an abortion is carried out. Saksone emphasises WHO guidelines, which recommend “removing medically unnecessary policy barriers to safe abortion, such as criminalisation, mandatory waiting times, the requirement that approval must be given by other people (e.g., partners or family members) or institutions, and limits on when during pregnancy an abortion can take place.”

The shockwaves of the Roe v. Wade reversal

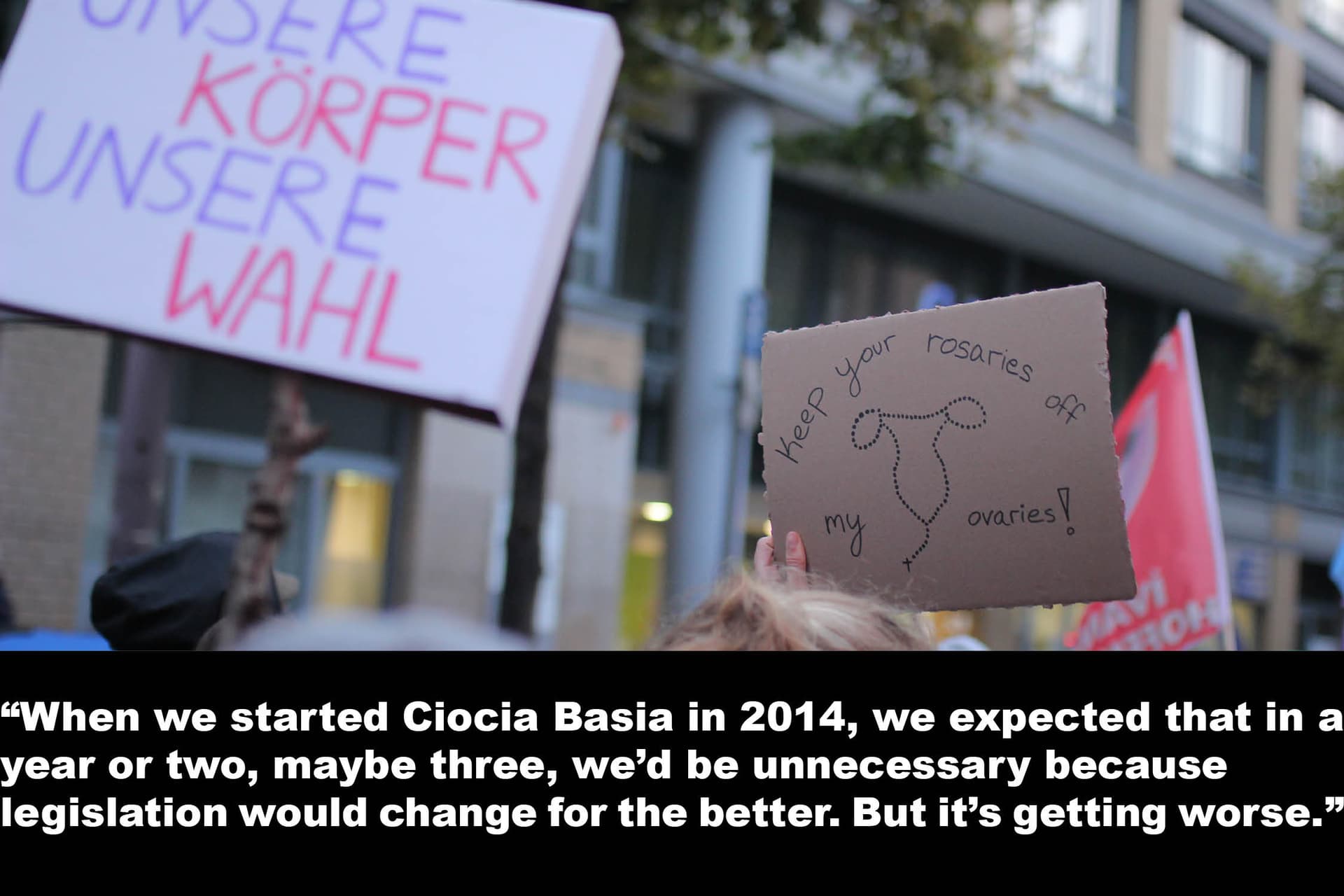

Predicting developments in legislation across Germany and Poland is a difficult business. As Dziuban notes, “When we started Ciocia Basia in 2014, we expected that in a year or two, we would be unnecessary because the legislation would change for the better. But it’s getting worse. I’d be afraid to predict the direction of the law change.”

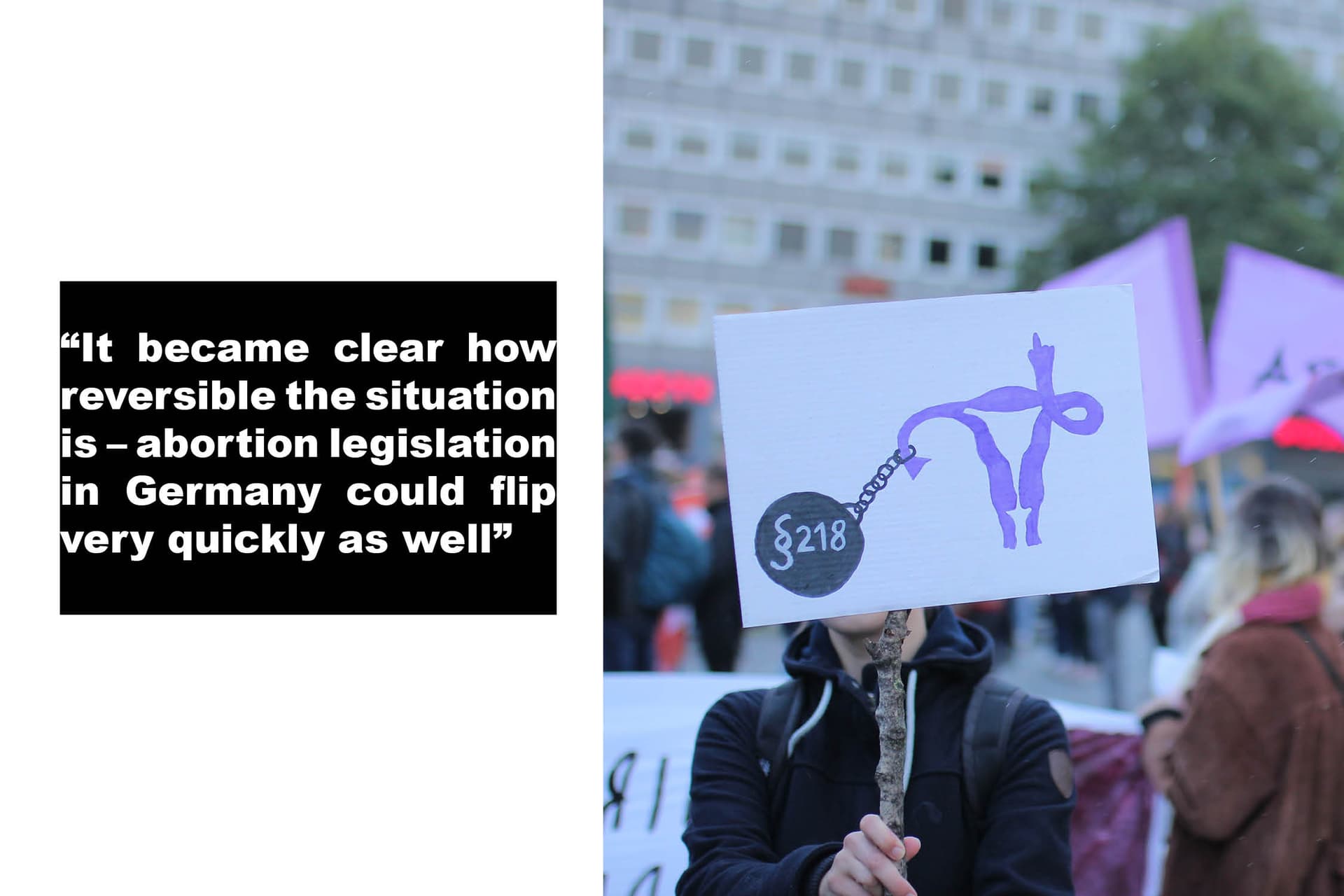

When Roe v. Wade was overturned in the US in June 2022, the reverberations were felt throughout Europe. “For many people, it became clear how reversible the situation is – the fact that abortion legislation in Germany could flip very quickly as well,” she continues. But as abortion rights debates intensify, awareness of Ciocia Basia and its sister organisations spreads. “Whenever there is a crisis about access to abortion, we do see an increase in support and solidarity from the international community. The tighter the laws become, the more the consequences become visible, the more support there is.”

Indeed, in November 2022, support among the Polish public for allowing access to abortion up to the 12th week of pregnancy rose to 70 per cent, the highest level ever recorded by pollster Ipsos. And increased funding has led to the growth of Abortion Without Borders, with new groups such as Ciocia Wienia in Austria and Ciocia Czesia in Czech Republic established, providing easier access to abortions abroad for people in southern or eastern Poland.

“Running through all these crises strengthens the ties in our network,” says Dziuban. “Abortion Without Borders has effectively taken over all the abortion work that was done before by the Polish healthcare system. We know we can rely on each other and share our resources and funding. The fact we are still here, and we manage, is a really great thing.”

Images:

Berlin. Courtesy of Bündnis für Sexuelle Selbstbestimmung (BfsS).

Safe Abortion Day Köln 2022. Courtesy of BfsS.

Courtesy of Ciocia Basia.

Safe Abortion Day Köln 2022. Courtesy of BfsS.

Safe Abortion Day Köln 2022. Courtesy of BfsS.

Safe Abortion Day Hamburg 2022. Courtesy of Adriana Beran, BfsS.

Graphics and layout by Graeme Bateman & Kolja Tinkova.