Student Internship position at Refuge Worldwide

Applications are now open for a studio and content based role.

Loading

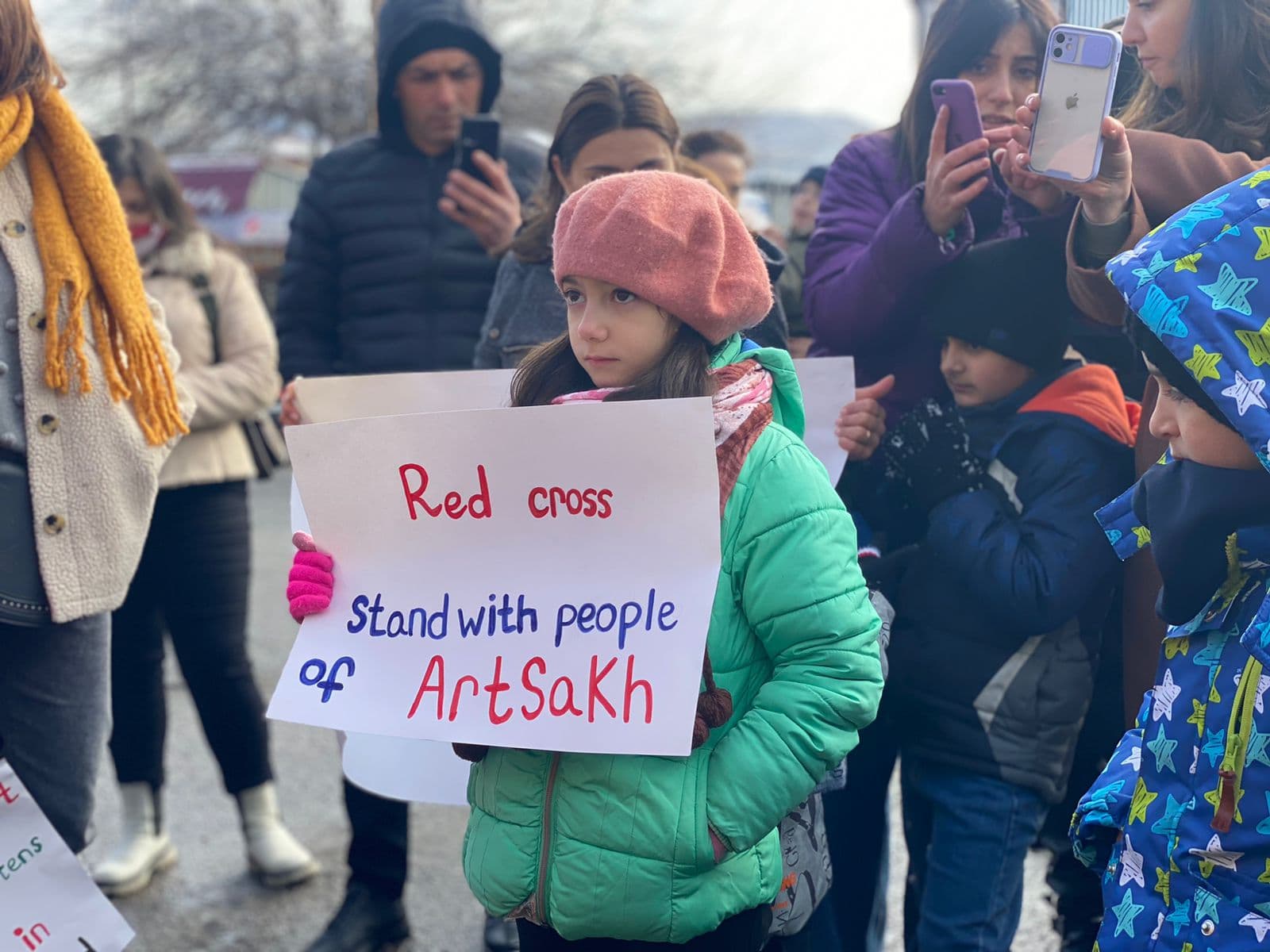

Living under a blockade.

By Johanna Urbancik

On 12 December, “environmental activists” from Azerbaijan blocked the only road connecting the breakaway Republic of Artsakh to Armenia, and to the rest of the world.

The road, called the Lachin Corridor, is still blocked over 100 days later. Artsakh, also known as Nagorno-Karabakh, has a majority ethnic Armenian population, who are currently being deprived of basic necessities and goods, such as food, medicine, and gas.

In 2020, Azerbaijan, with military assistance from Turkey, launched an attack on Artsakh and nearby territories, recapturing significant portions. Eventually, a ceasefire agreement was facilitated by Russia, and a peacekeeping force was deployed to monitor the remaining region. Pro-Armenian local authorities currently still govern the area.

The current blockade, now in its fourth month, is receiving very little media attention. Why is that? One can, of course, only speculate. Last year, the EU and Azerbaijan agreed on expanding the volume of gas exports from Azerbaijan to the EU, in order to stop importing Russian gas and actively funding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Armenia, on the other hand, is officially allied with Russia – at least on paper. The world’s indifference and Russia’s apparent unwillingness to unblock the corridor have made it easier for Azerbaijan to violate Armenia’s territorial integrity several times, violating the ceasefire agreement.

We spoke to Siranush Sargsyan, a historian and journalist based in Artsakh. She told us what it’s like living through this blockade and the ongoing threat of more violence and a third invasion.

How are you?

That’s a hard question, to be honest.

The blockade is already in its fourth month. Every day I see endless queues for food and other necessities. People wait in line and are forced to go home without nothing because of shortages. It's hard to follow because it’s hard psychologically to see what the people are going through.

During this period, Azerbaijan has cut off the sole gas supply to Artsakh several times. At this moment, the gas supply is once again disrupted. In addition to that, the main high-voltage electricity line has been intentionally damaged by Azerbaijan, who won’t allow our specialists to approach and repair it.

Because of this, we have very limited electricity and rolling blackouts. You can hear the sound of generators everywhere in the city. During the war the sound of the sirens was terrible, but now the sound of the generator does not give me peace – even during the night.

Living without electricity is very hard, especially in the winter. How are the people, and especially kids, coping?

In the 90s, when I lived through the first war, we had this same situation for almost two years. Nagorno-Karabakh was under a blockade, and we didn’t have access to Armenia or the outside world.

In Stepanakert, the capital of Artsakh, people were almost starving. Now, when I talk to the older generation they always compare these two events. Psychologically, I think they want to calm themselves down by thinking it was difficult back then, too, but we overcame it. The situation was different, though. We knew at the time what we were sacrificing and we had hope.

During that war when there was no electricity, it was cold and every pupil took a piece of wood with them to heat the school. When the blockade started in December, the government said they couldn't open the schools because of the weather and the risk of children becoming sick.

I asked myself, why were we able to manage back then, but not now? Just last month, the government solved this problem and installed wood-burning stoves, so even when there’s no electricity or gas, children can still go to school. I spoke to many kids who were excited about not having to go to school in the beginning. But now, they get stressed. The uncertainty is difficult for them. They know that their living conditions aren't normal, and they’re missing out on vital education. This blockade affects every person – no matter their age! They will remember this for the rest of their lives and live with this trauma forever.

Of course, considering they’ve already lived through a pandemic before this as well. I can’t even begin to imagine what kind of effect this will have on them.

Especially for children whose parents are stuck in Yerevan. There are some young kids who ask if they’ve done something wrong and if that's why their mother, for example, doesn’t want to come back to Artsakh. My nephew lost his father in the 2020 war, and now, he’s very scared of his mother leaving. He always asks when she’ll come back.

We don’t want him to understand what’s going on. I don’t want him to know that our neighbours are acting like that. I don’t want him to grow up with that resentment and hatred. I hope when he’s grown up, this situation will be different. We try to explain the blockade to him in different ways, but he doesn’t believe us, of course.

I want to discuss why Nagorno-Karabakh is currently under a blockade. Last year in December, a group of several hundred Azerbaijani citizens presenting themselves as "environmental activists" obstructed the Lachin corridor, ostensibly staging an environmental demonstration to draw attention to "eco-terrorism" in Karabakh.

Reports and investigations show that these protesters have very little to do with climate change but are actually acting in support of the regime in Azerbaijan. As reported in Azatutyun: "Data available in open sources proves that what many of [the 'protesters'] have in common is their love and support for the presidential family and pride in Azerbaijan’s military successes."

Are they still pretending to be environmental activists?

For us, it’s ridiculous they’re pretending to be environmental protesters.

After the war, we all knew that someday they’d close the road. We never thought they’d do it by making it an environmental issue. There are hardly any environmental protests in Azerbaijan.

We know that “normal” citizens from Azerbaijan can’t go to certain areas in Artsakh. It’s forbidden by the Azeri regime, and you need a special permit from the government. Even for journalists that’s the case. If there was a real environmental issue there, maybe we could understand them. But it’s all artificial and organized by the government.

They are mocking us. Not only by pretending to be doing it for the environment but by how they do it. On the first day, they blocked the road. On the second, they cut our gas supply. Then they damage our electricity and internet lines. Every day, they do something new. It feels like they’re testing us as if we’re animals. One day they come to a meeting to try to resolve issues, the next day they ambush and kill citizens. They leave no room for trust. These are clearly planned steps to deprive us of the right to live in our homeland. But we can't leave, and we don't want to leave!

Hypothetically, if you decided right now you wanted to leave. Would they allow you to?

I can’t leave, even if I wanted to. There’s one road. I want to have access to the road because some of my family and friends live in Yerevan. I don’t want to leave, but I want to have the right to come and go whenever I want, without facing any dangers.

The first thing I asked myself when they blocked the road was what I’d do if I were on the other side. I don’t know how I could’ve lived these past months without being able to go home. As long as Azeris are on the road, I cannot go there.

You’ve mentioned the Russian peacekeepers. Armenia is in an intergovernmental military alliance, CSTO, with Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan. Those Russian peacekeepers were supposed to prevent a blockade, which they’ve failed to do. What’s the purpose of those Russian soldiers?

In accordance with the ceasefire agreement signed on 9 November, 2020, the Lachin Corridor, which will ensure communication between Artsakh and Armenia, will remain under the control of the Russian peacekeeping contingent. By closing the only road connecting Artsakh to the whole world, Azerbaijan has violated that agreement, and Russia is not fulfilling its obligations.

I don’t understand why they don’t do anything, and why we have to pay for that in Nagorno-Karabakh? There is a treaty, so they should follow it. Why are our rights less than everyone else’s? Why is the whole world talking about the invasion of Ukraine, but not about us? We’re expected to be calm and wait. The Russians don’t help us, so should we just wait for the Azeris to come and kill us?

Did people generally expect the peacekeepers to fulfil their duties?

I know that for us, for Armenians, it was difficult that other peacekeepers would come here to protect us. But we accepted it, and we did our part, so they should do the same. I don’t have much hope now that the Russians will come and help us. I don’t have any hope about anyone coming to help us, including Western countries.

The only one we can count on is our compatriots living in Armenia and in different countries of the world. Most of whom – being the descendants of the Armenian Genocide – understand very well that today we too are under the threat of genocide.

Last September, ex-US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi visited Armenia. I guess she was one of the highest US-state officials to visit the country in the last few years. Has that visit changed anything for you, or was it purely performative?

Nancy Pelosi was always a friend of Armenian communities in the US. She has a good relationship with the descendants of the Armenian Genocide. Of course, she represents the US government. It was her last official trip, and she promised it to the Armenian community in the US. In the end, it came to nothing, though.

The US attitudes towards Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh are different. They made statements when Azerbaijan invaded Armenia in 2020, but they don’t say a word about Nagorno-Karabakh. The US government sends humanitarian aid everywhere, but what did they do during the Artsakh blockade? It’s like we don’t exist. We’re mostly invisible to this world.

Note: US-Secretary of State Antony Blinken has spoken to Azerbaijan’s president Aliyev on the 100th-day of the blockade. He pressed Aliyev to open the Lachin corridor. Asbarez reports Aliyev calling the blockade “false Armenian propaganda”, saying that Russian peacekeepers and the International Committee of the Red Cross have used the corridor. So far, no US sanctions have been imposed on Azerbaijan.

Why do you think that the situation is being ignored?

Azerbaijan is more of an ally and more valuable than Armenia to Russia, Europe and the West in general. The US uses Azerbaijan for their agenda and Europe wants to use Azerbaijan for their gas supply, regardless of the fact that Azerbaijan might be selling Russian gas to Europe.

I don’t know how to explain these feelings. Every time I hear EU president Ursula von der Leyen talk about the strength of Ukrainians, it makes me sad. I can imagine what Ukrainians are going through, I went through a couple of wars myself. I know how horrible and traumatic it is. But, I don’t understand why don’t European officials care about us too. Are we less brave? Are we less worthy to live in our land?

Of course, I don’t believe Russia will help us, and we all agree that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is wrong. But, when the Azeris invaded us in 2020, during the hardest year of the pandemic, it seemed to be okay for western countries as well.

For the whole world, it seems to be okay for us to be invaded. Why is one dictator a good, trusted partner, and the other one is evil?

I guess gas and politics are prioritised over morals and human rights.

We see that human rights and democracy are not actually that important to the West, and we’re disappointed. In the latest Freedom House Report, Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia are among the partly-free countries, and Azerbaijan is among the not free countries. How can the leading democratic countries turn a blind eye and throw us into the arms of tyranny?

It’s not even about recognising Nagorno-Karabakh, it’s about the people living here and their basic rights. For animals, when they’re living in bad conditions, there are organizations fundraising and trying to help. But when it’s 120,000 Armenians, there’s no outcry. I know that Nagorno-Karabakh isn't an exception. Many other places in the world are forgotten. You tend to see your pain first, though.

How can we help you?

I started writing after the 2020 war, as even before the blockade of Artsakh when the road was still open, it was closed to international journalists. They were forbidden to enter Artsakh.

For me, it was hard seeing so much suffering and pain, and also so many refugees after the war. People living here want to be heard and understood. I started to write about the people living here, but it is not enough. We need more international media attention.

You and others can tell the world about us and ask questions of your government's representatives. How is it that in the comprehensive agreement signed with Armenia in 2017 regarding the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, it is clearly stated that the issue should also be settled based on the principle of the right to self-determination? Today, everyone is silent about it.

The Nagorno-Karabakh problem is not solved, as Azerbaijan tries to present it. Through international media coverage, the world must understand that we are living in danger. We wish to have the opportunity to live in our historical homeland, but the sword of Damocles hangs over our heads. We live dreaming of peace but waiting for the next war.

Note: We have contacted the EU’s foreign minister Josep Borrell’s office and have asked Zane Rungule, who is responsible for Armenia and Azerbaijan, why the EU doesn’t have a clear stance on the blockade of the Lachin Corridor. So far, we have not received a response.

Since the invasion in 2020, Siranush has been writing about Artsakh for various international media outlets. Her work – and daily updates on life in Artsakh – can be checked out on her Twitter account at @SiranushSargsy1.

All images by Siranush Sargsyan. Graphics by Graeme Bateman.